This is an extract from the book “Gastroenterologia” written in 1956 by J. Groen and J.M Van der Valk.

In 1930 Cecil D. Murray, who was then still a medical student, published a most unusual paper in the American Journal of the Medical Sciences on the importance of “ Psychogenic factors in the aetiology of ulcerative colitis’’. From this original contribution has emerged the present so-called psychosomatic hypothesis, according to which ulcerative colitis, a severe organic disease of the colon, is considered to be the result of a specific emotional conflict, occurring preferably in individuals who are characterized by certain traits in their personality structure, which seem to make them more vulnerable to emotional trauma in their interpersonal relations.

Murray’s theory was based on the examination of few patients and we remember very well that on reading his paper we were not in the least convinced. The main reason why we began to investigate psychogenic factors in our own patients with ulcerative colitis was because, after having been disappointed by so many aetiological theories, we thought that this idea would be the easiest of all to disprove.

There was another reason for our scepticism, a reason which is still widely prevalent. It has become an almost unchallenged axiom of our 20th century medicine that psychogenic factors can produce functional diseases, but that organic disorders, characterized by morphological damage in the tissues, can be caused by organic pathogenic factors only. This axiom, which is of comparatively recent origin in Western medicine, is now so universally accepted that any observation which seems at variance with it, is regarded as a priori at fault, rather than as an indication that the axiom might be wrong.

Murray’s hypothesis about the aetiology of the disease challenged therefore not only all other theories, it defied a pillar of our 20th century medical thinking. No wonder that it gave rise to much controversy, a controversy which has not subsided since.

Yet it is a striking fact that of all those who have tried to repeat Murray’s work, not a single one, so far as we are aware, has failed to confirm his fundamental observation. Investigators differ in detail about the exact formulation of the personality structure that is supposed to form a predisposition for the disease. It is also a m atter of debate whether emotional conflict situations in themselves are re sponsible for every attack of ulcerative colitis or if they are only a precipitating factor when occurring together with some unknown organic agent. But in the main, the concept that ulcerative colitis is a psychogenic disorder stands undefeated.

The psychosomatic theory of the aetiology of ulcerative colitis can he formulated as follows:

1. Certain individuals possess in their personality structure a “ core'” of characteristics (partly inherited, partly developed under influence of certain youth situations), which make them more vulnerable than others to certain types of interhum an conflicts which threaten their emotional security, especially if these conflicts occur with “key-persons” in their close environment (parents, step parents, brothers or sisters, marriage partners, teachers, employers, colleagues, neighbours, etc.).

2. In the acute cases the disease breaks out after a latent period of not more than 24 or 48 hours, after such an individual has met a conflict, which is characterized by a coarse, usually verbal offence, a humiliation, often in the presence of others, which hurts the patient’s self-respect and leaves him defeated and humiliated. Often this gross offence refers to the inferiority of the individual concerning his sexual function. Recurrences follow similar offences, to which the patients seem to become more sensitive (by “facilitation”) as the disease proceeds.

In the eases of insidious onset, the conflict consists of a series of minor offences of a similar type, occurring in a life situation from which the individual cannot free himself.

3. Irrespective whether the feelings of humiliation and defeat are conscious or not, the emotional trauma is not discharged in lighting, weeping, speech or action. In other words, the individual does not respond, either by adequate or pathological, outwardly directed aggressive or defensive behaviour. This inhibition of a behavioral discharge converts the external interhuman trauma into an internal conflict situation. It is this emotional conflict within the individual which, through mechanisms and along pathways that are as yet insufficiently understood, produces the changes in the colonic mucosa that are responsible for the clinical and pathological signs of the disease.

According to this concept, ulcerative colitis is an organic disease with a predominantly psychogenic aetiology, a psychosomatosis. The relationship between the constellation of causal factors and the ensuing disease of the colon is considered to be specific in three respects:

1. Through some peculiarities of a predisposing personality structure, which makes the subject more vulnerable to

2. a certain environmental (interpersonal) stress-situation, against which

3. the individual does not (cannot) defend himself by action or words.

These three factors, although they can he distinguished, are mutually dependent.

The psychiatrically trained investigators are struck by the emotional immaturity, dependence, sensitivity, egocentricity and neurotic anxiety of these patients, and are inclined to classify most of them as rather severe cases of neurosis.

However, the personality structure of the patients also harbours more healthy features. Several of them show character traits of social value, provided the outward circumstances are favourable. In a harmonious setting many of them are active, sociable and lively, keen conversationalists with a good sense of humour. Often they have a good artistic taste and are conscientious and orderly workers. Difficult circumstances, however, easily create a situation to which they react with neurotic behaviour, which thus brings the underlying neurotic traits in the personality to the fore.

The patients are sensitive, even hypersensitive. A positive aspect of this is, that some of them are capable of artistic experiences; on the other hand, this hypersensitivity— in itself a non-specific neurotic trait—renders these subjects more vulnerable when confronted with difficult life situations. They cannot getover harsh treatment and feel easily offended, although this is often consciously denied.

From the psychiatric point of view they are infantile personalities. This means, amongst other things, that they are predominantly dependent and passive: they crave for affection, sympathy, admiration and protection without themselves giving much love and support to others. These passive features are in some, especially the male patients, more or less covered by an attitude of independence or even bragging, in imitation of other people rather than as a result of their own stability. This inclination to put up a show, not rarely leads them into a conflict which is more severe than they can handle. In such a situation the real dependency appears before long. Other patients choose the path of the least resistance and avoid or retreat from interpersonal situations that might involve fight and competition.

The patients are egocentric, which is also part of an emotional infantilism. The sphere of their affective interests seldom reaches further than that of family, relatives and a few friends. In contrast to what one finds in ulcer patients and hypertensives, these patients are rarely prominent or active members of clubs or societies. Lindemann pointed out that patients with ulcerative colitis depend for gratification in their inter-personal relationships on a few “key-persons’’ without whose affection and protection they cannot live. If something robs them of the love and support of one of these persons they have very few others on whom they can depend.

Although they may avow vague humanitarian ideals—also an expression of pseudoindependence—, this is practically all “ lip service” . Few of these ideals are acted out in reality. This may go to the point where they preach honesty and loyalty, but do not shrink from a lie when it suits their security-seeking purpose.

Their attitude towards the value of their own personality is hesitating and uncertain. Several of them strive consciously to be nice, good or modest, while, on closer observation, they appear vain, egoistic and extremelv touchy. Many of them harbour, under a show of pseudo-independence, marked feelings of inadequacy; often they admit suffering from feelings of inferiority. In other respects, however, they are highly pleased with themselves. Especially when judging people by their own limited code of moral standards, they consider themselves as meeting high requirements. As a result of this uncertain attitude the behaviour of some of our patients alternated from manifestations of ostentatious self-assertion and vanity, in a favourable environment, to expressions of inadequacy and dependence in a more difficult situation. This lability of social role made an uncertain and disagreeable impression on their environment.

Certain petty traits, mostly finical, are common in these patients. There is a marked tendency toward exaggerated decency in words and manners. They do not like vulgar or obscene expressions in conversation: they hate rough words and vulgar jokes. The tendency towards neatness is often displayed in their dress and the choice of their clothes. One may often recognize a colitis patient on the ward from the neat way he wears his pyjamas. Even in bed the patient wears a carefully selected and adjusted flower, brooch, handkerchief, or a scarf. Some of them have a flair for fashion in dress. Their carefulness often merges into meticulousness. In the choice of their friends or acquaintances, they often try to associate with people of a higher social rank, thus acquiring a stamp of distinction and respectability. Most patients have a great sense of cleanliness (except as far as it concerns their familiarity with their own excreta). The females arc compulsive and conscientious in the performance of their domestic duties, and in the upkeep of their furniture. Often they continue their work in the household for a long time, even alter the disease has considerably undermined their strength. In the male a certain pseudo-virility may or may not cover the same female “housekeeper-neatness ».

Groen in describing patients with ulcerative colitis, noted a lack of aggressive tendencies in their behaviour. In later investigations it became evident that the patients are inwardly often full of resentment and aggression, which are only poorly disguised under a seemingly non-aggressive behaviour. They are afraid, however, to act out or even show the aggression, for fear of creating a situation dangerous to themselves. In some of the patients their tendency to feign independence led to an occasional attempt at aggressive behaviour. However, as soon as they met resistance, especially from a strong opponent, they gave way.

The aggressive tendencies beneath the meek behaviour of these patients come out more freely when they are encouraged, during interviews, to express themselves. An eagerness to act out aggression when no longer checked by fear is also demonstrable during treatment. We have repeatedly had the opportunity to observe how these patients, kind and subdued initially, became unpleasantly aggressive to their fellow patients and the nursing staff, when they felt safe to do so under the physician’s protection. In two of our patients who became psychotic, the aggressiveness was also very pronounced.

Some patients found a safe outlet for their aggression in the form of gossiping. A characteristic feature was that they hardly ever attacked an opponent directly, but tried to do so via the intermediary of an authoritative and at the same time protective figure. They aimed at having their conflicts solved and their opponents rebuked for them by their father or mother, wife, husband or employer, or, in the hospital, by the physician or head-nurse. They complained and felt injustly treated when these persons were not willing to act out their aggression for them. This form of childish desire to remain protected and have an authoritative figure assume the aggressive role, is strikingly different from the competitive or aggressive tendencies which we found in the personality pattern of our peptic ulcer or hypertension patients.

The patients have a neurotic disturbance of their psycho-sexual development. They often have an exaggerated, idealistic, sometimes a positively naive and infantile conception of love. Males and females both think of love as a sublime adoration, attachment and harmony between husband and wife. Generally they consider the bodily sexual contact as something inferior. They are unable to establish a normal harmony between their erotic and ideal love-life. Owing to this, the patients are seldom capable of normal sexual relationships. Many of them never marry or marry only after long hesitation or long periods of engagement. Loss of libido or impotence frequently occurs in the male patients under the influence of an emotional disturbance. The female patients, if married, seldom experience a normal orgasm; frigidity preceding the onset of the disease is very common. Most women had a great fear of parturition; during pregnancy many of them suffered from hyperemesis.

From a psychiatric point of view, none of the behaviour patterns described is by itself characteristic of ulcerative colitis. Each of these “ traits” may also be found in cases of pure psychoneurosis, in other “psychosomatic” diseases and in a certain number of healthy individuals. The characteristic nature of the personality structure in ulcerative colitis is based therefore not so much on each single trait or behaviour pattern by itself, as on the combination of features in a certain proportion. Although patients suffering from other diseases may have some features in common with ulcerative colitis patients, there is a difference in quantitative mixing of the constituents of the personality, which is especially obvious in the adaptive mechanisms which these patients have utilized. Therefore, although it would be an exaggeration to speak of a completely fixed personality “type”, we consider that these common traits represent a specific “core” of the personality of patients with ulcerative colitis.

In this connexion we have to draw attention to the great influence of the disease, once established, on the personality. The tendency to dependence already present in these patients is greatly accentuated by the bodily illness, with its anaemia, dehydration, protein loss, frequent diarrhoea and abdominal pain, the frightening sight of blood in the stools, the depressing effect of the relapses, the limitation of food choice by the prescribed diet, the lack of gratification in work, the prolonged stay in the hospital with its forced dependence on others by bed rest, fear for the future and all the other unfavourable somatic and psychic influences. A certain regression into infantile attitudes and behaviour patterns occurs in the course of every illness: this regression becomes more marked when a disease causes pain and physical discomfort, is more prolonged and, in particular, when the prospects for recovery are poor. Patients with ulcerative colitis seem to regress more easily and to a greater extent than more normal individuals when they fall ill. As their personality was already weakly integrated, they can hardly adapt themselves to the illness in a constructive way. Their regression may become so marked that the selfish exacting behaviour, hypersensitivity and inability to adapt themselves to the situation of being a hospital patient, makes them lose the sympathy of the medical and nursing staff. Once they become aware of this, it has again an unfavourable influence upon their mental state and through this on their physical condition. Similarly it is a blow to them if the doctor instead of protecting them, lets them feel his disdain for their neurotic behaviour, or if a nurse should make a deprecating remark.

It should he stressed, however, that the personality core which has been described as characteristic for patients with ulcerative colitis, cannot he explained as a result of this regression alone. The biographies of the patients reveal abundant indications that this core was already present long before the illness began: as a matter of fact it could be traced in its development from childhood onwards. Likewise the follow-up of patients after they had recovered from the colitis showed that long after the patient was restored to normal life, the neurotic core still remained. The regression caused by the illness intensified some features of the personality structure, but did not produce it.

Psychological Tests. The finding of certain behaviour pat terns in the personality has been duplicated by the independent application of psychological tests, as c.g. the Rorschach test. It would go beyond the scope of this paper to present either the method itself or the statistical methods employed in evaluating the results in detail. It should be stressed however, that the finding of statistically significant differences between patients with ulcerative colitis and healthy control individuals or patients with other diseases, strongly confirms the original hypothesis as the method of psychological testing is more objective and independent of the psychiatric methods upon which the hypothesis was originally founded.

(c) History of Conflict Situations. In at least 80% of the cases a careful history reveals the presence of interhuman conflicts, provided the investigator possesses the skill and tactfulness required to obtain such inform ation. As precipitating factors M urray, Sullivan, Daniels, Palmer ,Groen, Paulley 11 and others have described acute emotional experiences of a certain type that have taken place 24 to 48 hours before the illness began. Usually the occurrence of such an event is denied, when the patients are asked outright during the first interview, if anything has upset them. When, however, they are given an opportunity to tell their life history privately and are encouraged to talk freely, they will “ naturally” come to tell of such events in subsequent interviews. The majority of the patients, however, are not prepared to accept even the possibility of a connexion between what they have gone through and their illness.

These conflicts have something in common. The patients were suddenly deprived of a loving care with which they had been surrounded: simultaneously these individuals who already doubted the value of their own personality, had to suffer an injury to their self- respect. Common to the humiliations the patients had undergone was the abrupt, harsh, often rude way in which this was verbalized. Many patients felt hurt particularly by the fact that this assault on their self-esteem took place in the presence of others, or that others knew or heard about it.

Not only the nature of this trauma, but also the attempt at solving it, was similar in all these patients. They tried to evade it in a manner that was in accordance with their character. Aggressive individuals, in a similar situation, would have taken action or would have attacked their opponents in an altercation or verbal outburst. Others would have complained to friends about the humiliation they had suffered, thus procuring themselves a defensive discharge of their feelings. In still others there might have occurred a depression or a hysterical reaction. But these patients reacted differently. Inwardly they continued to resent, but outwardly they tried to appear unaffected. They would admit neither to themselves nor to others, how much the conflict had humiliated them. They tried to conceal their weak and passive attitude from themselves and from their environment by not acting out. Rather than fighting for victory, escaping by flight, or acknowledging defeat, they tried to “ save face” by denying the importance of the conflict and by neither acting nor speaking about it. This evasion by showing an outwardly normal behaviour, this finding of a pseudo-solution, while the insufficiency of their personality had been so rudely revealed to them, this attempt to carry on while standing helpless in life—all this seems a typical reaction pattern of these patients.

(d) Physiological Observations. Following scattered observations that emotion can produce changes in the colour of the colonic mucosa in dogs (Drury, Florey and Florey; Liam) and in the human (White, Cobb and Jones; Almy and Tulin) Grace, Wolf and Wolff have studied the influence of emotional stimuli on the vascularity, tone, peristalsis and mucus secretion of the colon in human subjects. Their observations were carried out on four patients with colonic fistulas in whom segments of the mucosa that prolapsed through the abdominal wall, could be observed directly, and measurements could be made of the colour (indicating the degree of hyperaemia), size (tone), peristaltic contractions (measured by galloons introduced into the colon), visible haemorrhages and mucus produclion. They also determined the lysozyme content of the mucus obtained. Two of the patients thus studied had ulcerative colitis. By employing alternately neutral discussions and interviews about life stresses, a controlled laboratory study could be made of the behaviour of the colon under conditions of relaxation and of emotional tension. In addition, the reactions of the patients and their colonic mucosa were observed in response to situations of various nature that arose “spontaneously” during their stay in the hospital. Changes were found in all the colonic functions studied, under the influence of both spontaneous and induced emotional situations. It was also found that the response of the colon differed according to the emotion which the individual seemed to experience. Most important was the finding that, allhough all four subjects showed some reaction when in emotional tension, the changes were fundamentally of the same nature, but much more pronounced and sustained in the patients with ulcerative colitis, than in the other subjects.

Situations provocative of abject fear and dejection (abattement) were associated with hypofunction of the large intestine with pallor, relaxation, lack of contractile activity, and relatively low concentrations of lysozyme in the colonic secretions. Situations provocative of conflict with feelings of anger, resentment, and hostility, or of anxiety and apprehension were found to be associated with hyperfunction of the colon, manifested by increased rhythmic contractile activity with shortening and narrowing of the colonic lumen, hypermotility, and hypersecretion of lysozyme. Thick, tenacious mucous secretion was produced during anger and resentment, while a thinner, more watery secretion was associated with periods of relative tranquility, calm and security. Sustained peristaltic and tonic hyperfunction was accompanied in two subjects with intense hyperaemia and the appearance of petechial lesions, and in three subjects with an increase in the fragility of the mucous membrane. Mucosal erosions and ulceration in one subject with ulcerative colitis were observed to occur during a period of sustained conflict with feelings of hostility and frustration. These lesions receded during a period free of serious conflict.

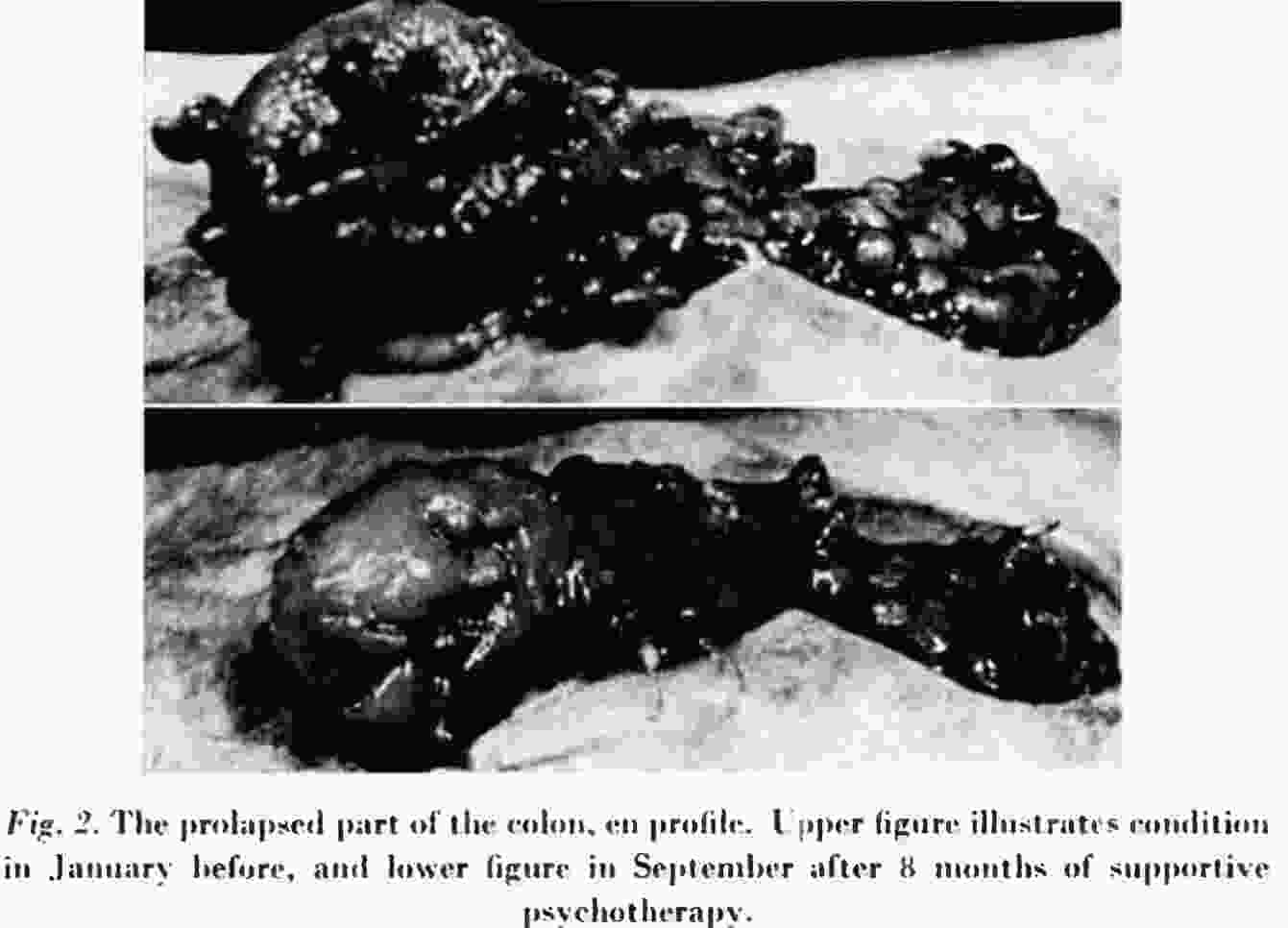

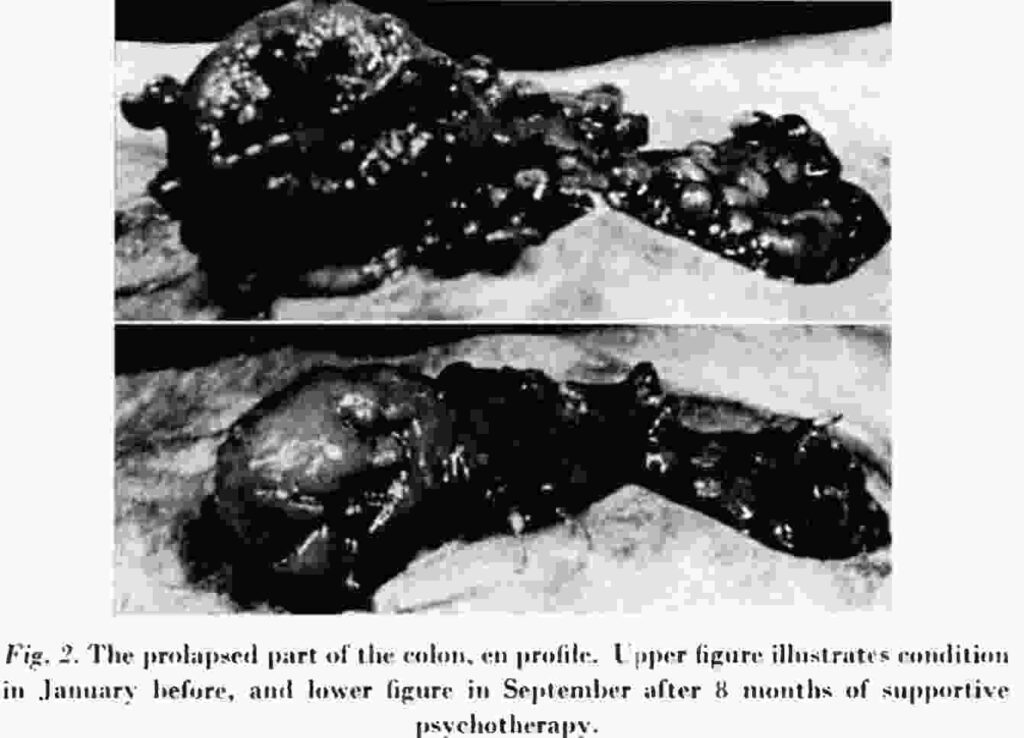

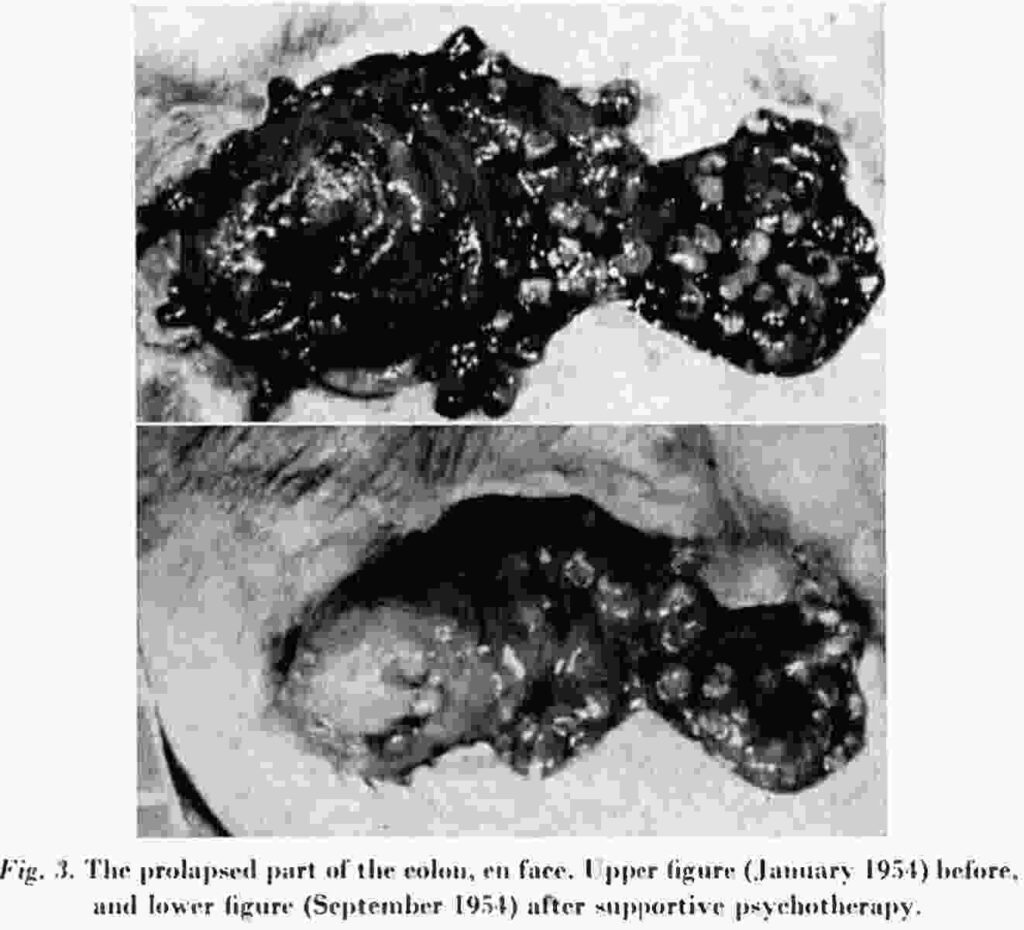

We have had an opportunity to carry out similar observations in one patient in whom a left-sided anus praeternaturalis had been performed elsewhere, without much success. The prolapsed colon showed hyperaemia, small haemorrhages and several pseudopolyps. There was hyperperistalsis with frequent bowel movements through the stoma, and the mucosa secreted mucus which was sometimes haemorrhagic; on a few occasions frank bleeding could be observed macroscopically in the hyperaemic mucosa (figs. 2 and 3).

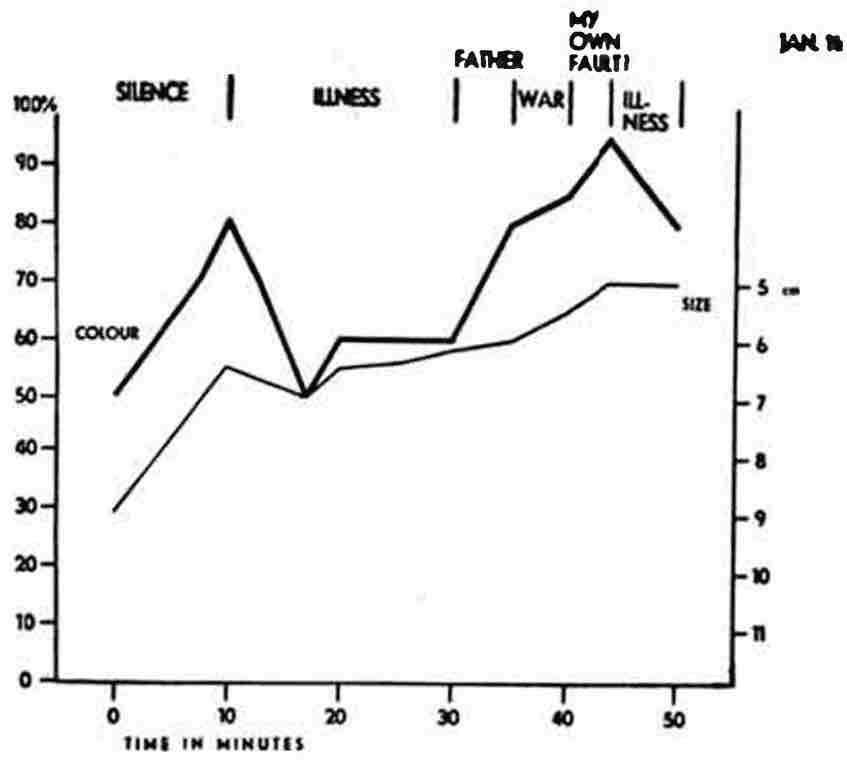

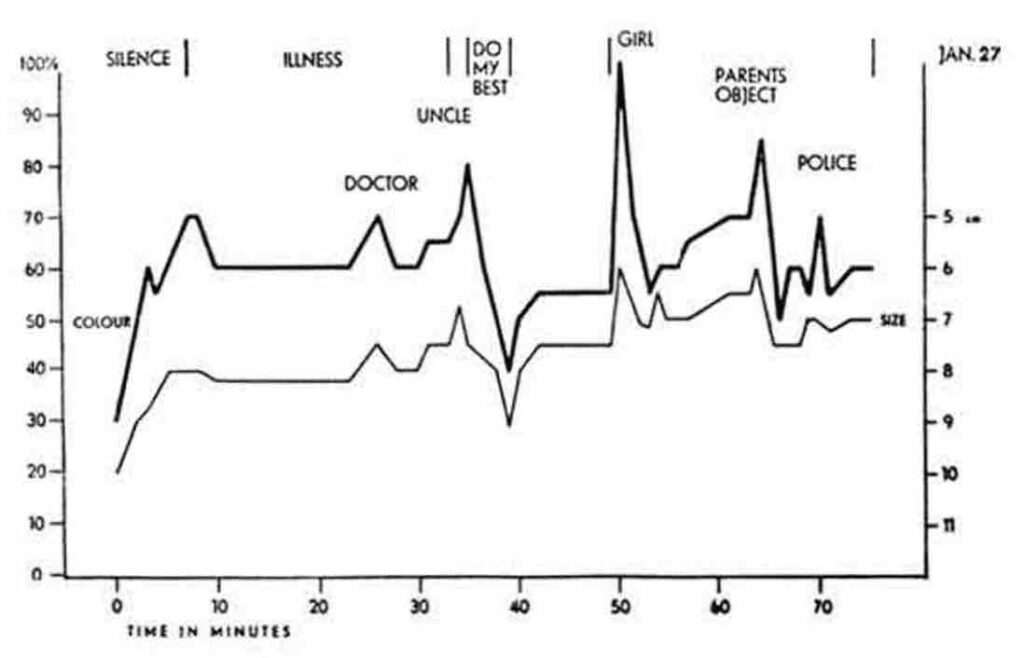

We found it difficult to interpret the individual’s feeling states during the conversations. He was reluctant to admit emotions in general and we have preferred therefore not to correlate the state of the colon with the subjective description of his emotions by the subject, but to restrict our observations to a study of a correlation between the topics of the conversation in which we engaged the patient and the behaviour of his colon. The methods of recording used were similar to those described by Grace et al. By comparing the colour of the prolapsed mucosa with a series of Talquist haemoglobin papers the degree of hyperaemia was expressed on a quantitative scale; by measuring the size of the prolapsed segment with a ruler a simple parameter of the contracture of the smooth muscle of the colon was obtained, which could be expressed in centimeters.

It was found (fig. 4) that when the patient was asked to relax on the couch and the investigator was observing the prolapsed mucosa without asking or saying anything at all, the colon became gradually more red, more contracted (smaller) with some increase in mucous secretion. The subject during this period of induced silence in the laboratory usually showed signs of rising tension and restlessness.

During the following conversations, some topics appeared to prevent this increasing hyperaemia and contraction of the colon and would even diminish the signs of colonic activity, if they were aroused by other stimuli: Speaking about his bodily complaints and other, purely medical aspects of his illness, or about his hobbies or about topics where the patient could “show off” by telling about successes, regularly had this “relaxing” effect. On the other hand when we introduced other subjects: his father, his uncle (his father’s partner in the management of a factory where the patient also worked and of which he hoped, but was uncertain, that one day he would become a director himself), the surgeon who had operated on him, or a girl in the factory with whom he had had a secret love affair, the intestine became hyperaemic, contracted and discharged its content, whereas the secretion of mucus increased. This was, in the first interviews, associated with the appearance of haemorrhagic streaks on the surface. It is of interest to mention a marked hyperaemia and contraction of the bowel when he told that he had once been surprised by a policeman while he was in a hidden place with the girl and that he had broken off his relation with her after their affair was discovered and he had been ridiculed because of her lower social and cultural status (fig. 5). His illness had started “just about the time when this happened”.

(d) Results of Psychotherapy. Improvements, sometimes leading to clinical cures, have been observed to occur “spontaneously” when the patient’s life situation changed for the better. This is an old clinical observation. The relationship between life events and “spontaneous” remissions, however, will only be evident to those investigators who do not restrict their observations to the colon. Conscious efforts at psychotherapy by various authors have shown that a number of patients improve after a supportive form of psychotherapy, which is characterized by sympathetic listening and the giving of constant care, protection, sympathy and appreciation in frequent interviews of preferably every day. It is not the purpose of this paper to outline in detail the type of psychotherapy which must be given to these patients. But it serves as support for the psychosomatic hypothesis that the percentage of favorable results is of the same magnitude as claimed for the various medical or surgical methods at present commonly used. Our personal experience concerns a series of cases which have been treated almost exclusively by a supporting form of psychotherapy. This was done in an attempt to evaluate the effect of psychotherapy, supplemented only by general medical measures. Patients were treated with bed-rest when they were in a serious condition and, if necessary, with rehydration and bloodtransfusion. They were put on a full diet, which sometimes required considerable explaining and encouragement. Drugs were not given in any form throughout this therapeutic experiment. The patients were observed during the years 1939 to 1949 and have been followed up to 1952 ( Groen and Bastiaans). Table 1 summarizes these results, together with a similar therapeutic experiment of Grace et al. and of Paulley. Table 2 contains a summary of a smaller recent series, started in 1953 in which the results of psychotherapy were compared to those of a similarly composed series undergoing surgical treatment. The experiences of Paulley similarly confirmed the hypothesis: If no psychogenic factor were at play pure psychotherapy would have been predicted to have had less effect than “organic” treatment.

More evidence is needed before the psychosomatic theory can be considered proven, but it offers interesting possibilities for further research. Above all it contains a promising approach for a therapy, provided the doctor has enough time available and is able to oveccome the (understandable) aversion and impatience which sufferers from psychogenic disorders often provoke in him. If one can overcome this, the simple form of “ psychotherapy” is not difficult and is indeed only a somewhat more specialized form of ordinary medical care and encouragement. In practice this supportive psychotherapy should not be aimed at finding out the causative conflict at all cost; the story should come out “naturally” or not at all, if only the main purpose, support, is achieved. This psychotherapy can be combined with (but cannot be replaced by) the application of small doses of ACTH or corticoid compounds, dietetic measures, fluid, electrolytes, and blood replacement, etc. Above all we wish to emphasize that the psychotherapy of ulcerative colitis should not be put off as a last resort, when the condition has become alarming. Neither must the patient necessarily be transferred to the care of the psychiatrist. Early psychotherapy by his own doctor might further improve the results and furnish more support for the psychogenic aetiology.

Thus, if Murray had done nothing else but open this perspective of a cure, without the mutilating operations that are still carried out for this fundamentally non-malignant condition, he would have deserved our gratitude and admiration.